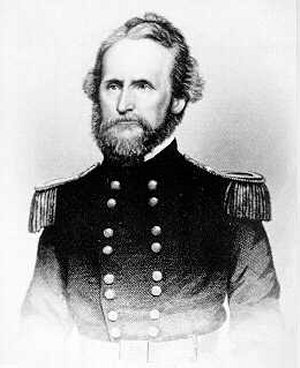

Nathaniel Lyon

(July 14, 1818 - August 10, 1861)

(July 14, 1818 - August 10, 1861)

Nathaniel Lyon was a controversial figure that played a key role in the early struggle for Missouri during 1861. A West Point graduate, Lyon rose to the rank of Brigadier General in the United States Army. On August 10, 1861 at the Battle of Wilson's Creek, he became the first Union General to be killed in action during the Amercian Civil War.

Pre-Civil War Role

Nathaniel Lyon was born on a farm in Ashford, Connecticut on July 14, 1818.

Lyon was only nineteen, five feet five inches tall, and weighed 130 pounds when he entered The Military Academy at West Point on July 1, 1837. He graduated 11th out of a class of 52 on June 22, 1841.

Owing to his ambitious nature and his rigid beliefs regarding right and wrong, Lyon's temper often got him into trouble with his military superiors. He was court-martialed once and disciplined several other times. His superiors found him quick tempered and rash in his judgment. After his tour of duty was up, Lyon had made a decision to leave the military. This changed when the war with Mexico started.

Lyon was adamantly opposed to forcibly annexing Mexican territory in to the United States. However, once war seemed inevitable, Lyon was ready and enthusiastically proceeded with his unit to Texas. He arrived in October 1846. Lyon soon became disillusioned with and began to criticize his army's commander, General Zachary Taylor. Later that year, General Winfield Scott would be sent to Mexico to lead an invasion of the eastern coast. Lyon's Second Infantry Regiment was ordered to Tampico, Mexico and would be part of the invasion force. In 1847, Lyon was promoted to first lieutenant for "conspicuous bravery in capturing enemy artillery" at the Battle for Mexico City and received a brevet promotion to captain for his actions at Contreras and Churubusco. Lyon's personality seemed better suited to war than to peace. In July 1848, Lyon's regiment returned to the United States.

Lyon was adamantly opposed to forcibly annexing Mexican territory in to the United States. However, once war seemed inevitable, Lyon was ready and enthusiastically proceeded with his unit to Texas. He arrived in October 1846. Lyon soon became disillusioned with and began to criticize his army's commander, General Zachary Taylor. Later that year, General Winfield Scott would be sent to Mexico to lead an invasion of the eastern coast. Lyon's Second Infantry Regiment was ordered to Tampico, Mexico and would be part of the invasion force. In 1847, Lyon was promoted to first lieutenant for "conspicuous bravery in capturing enemy artillery" at the Battle for Mexico City and received a brevet promotion to captain for his actions at Contreras and Churubusco. Lyon's personality seemed better suited to war than to peace. In July 1848, Lyon's regiment returned to the United States.

Lyon would next accompanying the Second Infantry Regiment to its new post in California. A detachment containing Lyon was sent to San Diego. In the summer of 1849, there were two isolated incidents in northern California in which Native Americans had killed white settlers and an army officer. The government decided punitive actions were necessary, and circumstances put Brevet Captain Nathaniel Lyon in charge of the punitive expedition. The orders stated that the expedition was "...to chastise the authors of both outrages ... and to strike them promptly and heavily."

By the time Lyon's force had reached Clear Lake, the Native Americans had fled to a small island at the north end of the lake. Lyon crossed over to the island, and by the time they were through, Lyon and his forces had killed between 200 and 400 Native Americans, many of them women and children. Lyon did not suffer a single loss from his force. Lyon net moved on to determine who had murdered the army officer. He captured two local Native Americans who led him to an island on which was located a tribe suspected of the crime. Lyon surrounded the tribe and then attacked. According to Lyon, the island "soon became a perfect slaughter pen, as they continued to fight with great resolution and vigor till every jungle was routed." Close to 100 Native Americans were killed while two men from Lyon's force were wounded. After returning to his base, Lyon received a special commendation for his performance. In 1851, Lyon received a promotion to full Captain.

Lyon's company was sent to Fort Riley, Kansas and arrived there in May 1854. Lyon would soon find himself in the middle of "Bleeding Kansas." Dr. William A Hammond, a close acquaintance of Lyon's during his time at Fort Riley later wrote the following about him:

"I have never in the whole course of my life met with a man as fearless and uncompromising in the expression of his opinions, and at the same time so intolerant of the views of others, as was he."

While at Fort Riley, Lyon once again ran into difficulties with his superior officer, in part because of the brutal punishments Lyon inflicted on the soldiers at the fort for their infractions. The disagreements would continue and Lyon initiated charges against his superior officer that ultimately led to his superior's dismissal from the army.

Lyon also was opposed to the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 and blamed southerners for its passage. During the Kansas territorial elections held in 1855, Lyon to an active role near Fort Riley to ensure that free-soilers would win the day. Lyon was anti-slavery but did not consider himself an abolitionist. Lyon was not interested in granting slaves their freedom. He was opposed on more practical grounds:

"... We have opposed its [slavery's] extension into our territories because of its injurious effects upon the free laborer, and consequent diminution of the productions of labor. ... We are to have a final settlement of this question, by a new construction of the Constitution, give an express recognition of the right of property in slaves in the States where it now exists, or may hereafter exist."

Early in 1855, Lyon wrote to a friend that "the aggressions of the pro-slavery men will not be checked, till a lesson has been taught them in letters of fire and blood."

The ensuing Missouri-Kansas border war would send Lyon's Company down to Fort Scott, Kansas. They would arrive there in June 1858. Lyon's personal views would have him place the blame for the problems in southeastern Kansas on the pro-slavery factions. The presence of the Federal troops did appear to stabilize the situation, at least temporarily, and Lyon returned to Fort Leavenworth in August.

Becoming increasingly disillusioned with the Democrats, Lyon had become an active supporter of the newly formed Republican party. He was invited to become a member of the Wide Awakes, a paramilitary campaign organization affiliated with the Republican Party during the 1860 election. Upon joining, Lyon had pledged to do everything he could to uphold the principles of the Republican party's cause.

In the fall of 1860. Lyon was reassigned to Fort Scott, Kansas on the orders of the new commander of the Department of the West, Brigadier General William S. Harney. Because he was from Tennessee and owned slaves, Lyon immediately labeled Harney as pro-southern. Lyon believed Harney would lay the entire blame for the border problems on the free-soilers.

In the fall of 1860. Lyon was reassigned to Fort Scott, Kansas on the orders of the new commander of the Department of the West, Brigadier General William S. Harney. Because he was from Tennessee and owned slaves, Lyon immediately labeled Harney as pro-southern. Lyon believed Harney would lay the entire blame for the border problems on the free-soilers.

Harney ordered Lyon to Mound City, Kansas to arrest the free-soil leaders, James Montgomery and Charles Jennison. Both had been leading particularly destructive and brutal raids across the border into Missouri. After arriving in Mound City, Lyon actually met with Montgomery and they hatched a plan. Montgomery would leave the area temporarily. Lyon would bring his forces to Montgomery's home and conduct a search for him. Lyon would also conduct a search at Jennison's home. Then after not finding either of them, Lyon would return to Fort Scott. Eventually, Harney returned to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas and left Lyon in command at Fort Scott. While in command there, South Carolina voted to secede from the Union and war would not be far off. In January 1861, Lyon's Company was ordered to join the garrison at the Federal Arsenal in St. Louis, Missouri.

Civil War Role

Although the majority of the citizens of St. Louis, Missouri had northern sympathies, the more rural counties along the Missouri River were sympathetic with the southern cause. Indeed, this area in the Missouri River Valley was known as "Little Dixie." This area had been settled in the early 19th century by emigrants from southern states. Little Dixie had the state's highest concentration of slaves. Although the majority of Missourians preferred to remain "neutral" in the approaching conflict and be left alone, the recently elected Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson was decidedly aligned with the southern cause.

Although the majority of the citizens of St. Louis, Missouri had northern sympathies, the more rural counties along the Missouri River were sympathetic with the southern cause. Indeed, this area in the Missouri River Valley was known as "Little Dixie." This area had been settled in the early 19th century by emigrants from southern states. Little Dixie had the state's highest concentration of slaves. Although the majority of Missourians preferred to remain "neutral" in the approaching conflict and be left alone, the recently elected Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson was decidedly aligned with the southern cause.

The St. Louis community was dominated by German immigrants who were uncompromising in their support for the Union. Another smaller, radical group was called the "Unconditional Unionists." Many in this groups were former members of the Wide Awakes, which had disbanded after helping to elect Abraham Lincoln. The leader of this radical group was Frank P. Blair, Jr., who was an influential member of the Republican Party. The Germans formed groups called Turner Societies and pledged to defend the Union by whatever means necessary. They began drilling and arming themselves. Blair worked to obtain arms for them.

The St. Louis community was dominated by German immigrants who were uncompromising in their support for the Union. Another smaller, radical group was called the "Unconditional Unionists." Many in this groups were former members of the Wide Awakes, which had disbanded after helping to elect Abraham Lincoln. The leader of this radical group was Frank P. Blair, Jr., who was an influential member of the Republican Party. The Germans formed groups called Turner Societies and pledged to defend the Union by whatever means necessary. They began drilling and arming themselves. Blair worked to obtain arms for them.

Meanwhile, individuals supporting secession also began to form quasi-military groups and called themselves the "Minute Men." They began to plan a takeover of the St. Louis Arsenal in order to capture the large quantities of military stores there. The arsenal was guarded only by a handful of Federal soldiers. Blair found out about the plans by the Minute Men to take over the arsenal. Blair's connections in Washington resulted in Lyon being transferred to St. Louis with his men to reinforce the arsenal's garrison. Lyon and Blair would meet soon after Lyon arrived in St. Louis. They immediately became close confidants. Blair used his contacts in Washington to get Lyon appointed as commander of the arsenal. Lyon had other supporters who were arguing for this on his behalf. As Blair prepared to travel to Washington to serve as a US Congressman from Missouri, he obtained Lyon's commitment to help arm and train the Germans in what were now being called the Union Guard (Blair had also worked to gain the commitment of Franz Sigel to help train the Union Guard).

While in Washington, Blair met with President Lincoln and convinced him that Lyon needed to be given command of the St. Louis Arsenal. Lyon immediately started fortifying the arsenal's defenses. While this was happening, the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861 and the war had started. On April 15th, President Lincoln issued his call for 75,000 volunteers.

In response to the beginning of hostilities in the east, tensions in St. Louis rose and there was increased activity by the militia groups on both sides. On April 17th, Governor Jackson condemned Lincoln's call for volunteers from Missouri:

"Sir, ... your requisition in my judgment, is illegal, unconstitutional and revolutionary in its object, inhuman and diabolical, and cannot be complied with. Not one man will the state of Missouri furnish to carry on such an unholy crusade."

Lyon was outraged by the attack on Fort Sumter. He immediately increased the security at the St. Louis Arsenal. In response, Governor Jackson ordered the commanders of the Missouri State Guard in St. Louis to assemble their militiamen for drilling. Congressman Frank Blair returned from Washington with an order approving the issuance of arms to any of the Union Guard that mustered into the Union Army as Missouri volunteers. However, this was being blocked by General Harney who said this had to authorized by Governor Jackson. Blair immediately went to his political contacts in Washington to bring about the removal of Harney.

Lyon was outraged by the attack on Fort Sumter. He immediately increased the security at the St. Louis Arsenal. In response, Governor Jackson ordered the commanders of the Missouri State Guard in St. Louis to assemble their militiamen for drilling. Congressman Frank Blair returned from Washington with an order approving the issuance of arms to any of the Union Guard that mustered into the Union Army as Missouri volunteers. However, this was being blocked by General Harney who said this had to authorized by Governor Jackson. Blair immediately went to his political contacts in Washington to bring about the removal of Harney.

The US War Department had sent one Lieutenant John M. Schofield to be the mustering officer in Missouri. Lyon and Blair worked with Schofield to muster in and arm the volunteers. While Schofield mustered in the recruits, Lyon received a telegram from Washington:

The US War Department had sent one Lieutenant John M. Schofield to be the mustering officer in Missouri. Lyon and Blair worked with Schofield to muster in and arm the volunteers. While Schofield mustered in the recruits, Lyon received a telegram from Washington:

"General Harney has this day been relieved from his command. The Secretary of War directs that you immediately execute the order previously given to arm the loyal citizens, to protect the public property, and execute the laws. Muster four regiments into service."

The next day, Lyon received another telegram from Washington placing him in complete command of all Federal forces in St. Louis. Within a week, the four regiments had been raised and they had elected Lyon as their general. Frank Blair was elected Colonel of the 1st Regiment, Missouri Volunteers. Lyon was officially named Brigadier General of the Missouri Volunteers.

Missouri Governor Jackson was working behind the scenes to align Missouri with the Confederacy. He had been in contact with Jefferson Davis and has gained his commitment to send four artillery pieces to the Missouri State Guard in St. Louis. On April 22, 1861, Jackson ordered all state militia unit to meet in their districts on May 3, 1861. In St. Louis, the militia district commander, Brigadier General Daniel M. Frost, established an encampment at Lindell Grove (the current campus of St. Louis University on Lindell Boulevard) in the western part of St. Louis. There were close to 900 men encamped at what they dubbed "Camp Jackson."

Missouri Governor Jackson was working behind the scenes to align Missouri with the Confederacy. He had been in contact with Jefferson Davis and has gained his commitment to send four artillery pieces to the Missouri State Guard in St. Louis. On April 22, 1861, Jackson ordered all state militia unit to meet in their districts on May 3, 1861. In St. Louis, the militia district commander, Brigadier General Daniel M. Frost, established an encampment at Lindell Grove (the current campus of St. Louis University on Lindell Boulevard) in the western part of St. Louis. There were close to 900 men encamped at what they dubbed "Camp Jackson."

Lyon, of course, kept a close eye on what was going on at Camp Jackson. Lyon considered it to be a camp full of traitors to the Union. He began planing to neutralize the militia at Camp Jackson. On May 10th, Lyon moved against the encampment with 6,000 to 7,000 men and surrounded it on three sides a little after 3:00 in the afternoon. Because they had not completely surrounded Camp Jackson, about one third of the militia were able to escape. Lyon sent a message to Frost demanding his surrender. Outnumbered eight or nine to one, Frost had no choice but to surrender. Lyon offered then parole if they would swear an oath of allegiance to the United States. Since only ten men accepted this offer, Lyon marched the rest (669 men), under guard, through the city streets back to the arsenal.

There were a great many onlookers watching the procession. The pro-Southern onlookers were hurling insults at the Federal soldiers. Eventually, they began to throw things at the soldiers. Someone in the crowd fired a pistol at the Federals. Additional shots were fired. The German recruits responded by firing into the crowd of onlookers. Eventually, Lyon was able to get his troops under control. Twenty-eight civilians were killed and around 75 were wounded. Two Federal soldiers were killed along with three of the prisoners. The "Camp Jackson Affair" received a lot of publicity and greatly increased the tensions in Missouri. Many Missourians who had been neutral came out in favor of the southern Confederacy. Former Missouri Governor Sterling Price was once of these. He had actively supported Missouri neutrality, but now offered his services to Governor Jackson. On May 12th, Jackson appointed Price as Major General in command of the Missouri State Guard.

There were a great many onlookers watching the procession. The pro-Southern onlookers were hurling insults at the Federal soldiers. Eventually, they began to throw things at the soldiers. Someone in the crowd fired a pistol at the Federals. Additional shots were fired. The German recruits responded by firing into the crowd of onlookers. Eventually, Lyon was able to get his troops under control. Twenty-eight civilians were killed and around 75 were wounded. Two Federal soldiers were killed along with three of the prisoners. The "Camp Jackson Affair" received a lot of publicity and greatly increased the tensions in Missouri. Many Missourians who had been neutral came out in favor of the southern Confederacy. Former Missouri Governor Sterling Price was once of these. He had actively supported Missouri neutrality, but now offered his services to Governor Jackson. On May 12th, Jackson appointed Price as Major General in command of the Missouri State Guard.

In order to buy time, Jackson sent Price to meet with Harney and negotiate a "truce." Harney had been reappointed as commander in St. Louis by General-in-Chief Winfield Scott. Price and Harney met on May 20th and drafted a formal agreement. It said that Missouri would be responsible for maintaining order in the state and that Harney would not use Federal troops for this purpose as long as order was being maintained. Both Blair and Lyon were incensed by the agreement. On May 30th, Harney, once again, was relieved of command. Lyon, once again, was placed in command of the Department of the West.

As a last ditch effort to preserve the peace in Missouri a meeting was arranged between Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon, Congressman Frank Blair, Major General Sterling Price and Governor Claiborne Jackson. The meeting was to be held in St. Louis at the Planter's House Hotel and Lyon guaranteed safe passage for both Price and Jackson. On June 11, 1861, after several hours of contentious discussion, Lyon stood up and declared,

"Rather than concede to the State of Missouri the right to demand that my government shall not enlist troops within her limits, or bring troops into the State whenever it pleases, or move troops at its own will into, out of, or through the State; rather than concede to the State of Missouri for one single instant the right to dictate to my government in any matter, however unimportant, I would see you, and you, and you, and you, [pointing to each man in the room] and every man, woman, and child in the State dead and buried. This means war. In an hour one of my officers will call for you and conduct you out of my lines."

Lyon walked out of the meeting. Missouri would soon be at war. Price and Jackson quickly left St. Louis for Jefferson City to begin preparing for war. Price convince Jackson that Jefferson City had to be abandoned because it was not easily defended. They went up the river to Boonville, Missouri.

Lyon worked with Schofield and Blair to prepare a plan to capture the Missouri State Guard. Lyon would take his main force west along the Missouri River and pursue the Missouri State Guard to Springfield, Missouri. A smaller force under Thomas Sweeny would head for Springfield via Rolla, Missouri to prevent any movement of Confederate forces from Arkansas. Lyon loaded about 2,000 troops onto steamboats and headed for Jefferson City, Missouri. Upon finding that the Price and Jackson were not there, he left a small force to occupy the state capital and continued on to Boonville with about 1,700 men.

When Jackson and Price arrived in Boonville, Price realized that their best hope was to prepare for a delaying action against the Federals before withdrawing south and west. The Missouri State Guard was still too green and too poorly armed to be an effective fighting force. However, Price was quite ill and left the Missouri State Guard under the command of Governor Jackson while he went to recuperate at his home in Keytesville, Missouri.

On June 17, 1861, Lyon's troops disembarked and marched toward Boonville. They encountered pickets as they approached the bluffs, but Lyon deployed skirmishers and pushed his men forward rapidly.

On a ridge behind the bluff waited a few hastily formed and ill-equipped companies of the Missouri State Guard, totaling about 500 men with no artillery. Lyon deployed his men and artillery and advanced. The artillery soon displaced Missouri State Guard sharpshooters and the Union infantry closed with the line of guardsmen and fired several volleys into them, causing them to retreat. This portion of the fighting lasted only 20 minutes. Some attempts were made to rally and resist the Federal advance, but these collapsed when a flanking Union company seized the camp behind them, and a siege howitzer on one of Lyon's riverboats began shelling the Missouri State Guard positions.

The Missouri State Guard retreat rapidly turned into a rout. The guardsmen fled back through the town of Boonville. Some headed for home, but most joined the Governor in retreating to the southwest corner of the state. The short fight and precipitate retreat gained the nickname "The Boonville Races." Lyon took possession of the town at 11:00 A.M.

The Missouri State Guard had escaped, but it was badly dispirited by this early defeat. Lyon's victory gave the Union forces time to consolidate their hold on the state. Lyon's victory also brought him the attention of Union supporters beyond the Missouri border. It was a great strategic victory for the Union at Boonville, for Lyon had secured the Missouri River for the Union. But Lyon was not satisfied with a strategic victory. He wanted to punish the secessionists.

Supply problems kept Lyon from being able to leave Boonville as quickly as he would have liked. Price and Jackson were able to march further south to safety. Lyon was finally able to depart from Boonville on July 3rd.

About this time, John Charles Fremont was appointed as the commander of the Department of the West.

About this time, John Charles Fremont was appointed as the commander of the Department of the West.

While struggling to get his forces across the flooded Grand River, Lyon received word of Sigel's defeat at the Battle of Carthage. Once across the river, Lyon moved with haste for Springfield, Missouri. He arrived on July 13, 1861. His men were tired and poorly supplied. He soon found out that the Missouri State Guard was nearby and had him outnumbered. Confederate forces under the command of Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch were also in the area.

Believing that he was greatly outnumbered, Lyon sent dispatches to Fremont and Washington requesting supplies and reinforcements. Lyon was passionate in thinking that the fate of holding onto Missouri for the Union hung in the balance. There would be no reinforcements and supplies were slow in coming.

Lyon left Springfield in order to engage the Southern forces. On August 2nd, his cavalry advance guard encountered the enemy near Dug Springs, Missouri. The Federals were victorious but Lyon now knew that Price had been joined by McCulloch's Confederate forces. He was outnumbered two to one. Lyon decided to withdraw his forces back to Springfield.

Lyon was not sure what his next steps would be. Lyon was seriously considering withdrawal from Springfield. His troops were in poor shape. Many of his forces were nearing the end of their enlistments. His army was low on supplies. He was outnumbered by at least two to one. But Lyon feared that if he retreated, the Confederates would attack him and he would not be in a position to defend against that attack. So Lyon decided to take the initiative and attack the Confederates.

Lyon began moving his forces south on the evening of August 9, 1861. They were headed for Wilson's Creek where the enemy was encamped about 10 miles southwest of Springfield. Lyon had decided to split his forces and sent Colonel Franz Sigel's Brigade around the Confederate position in order to attack them from their rear.

Lyon began moving his forces south on the evening of August 9, 1861. They were headed for Wilson's Creek where the enemy was encamped about 10 miles southwest of Springfield. Lyon had decided to split his forces and sent Colonel Franz Sigel's Brigade around the Confederate position in order to attack them from their rear.

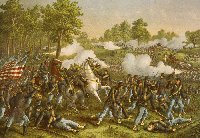

At daylight on August 10th, the Federal troops began to move forward. First contact was made with units of the Confederate cavalry acting as an advance guard. Sigel, too, had begun his movement at daylight to the south of the Confederate camps. His position was on the top of a small hill that gave him an unobstructed view of the Confederate camps. The Confederate commanders were surprised by the Federal attack, but quickly reacted and got their forces into line of battle to fend off the Federal attack..

After initially withdrawing in front of the Federal attack, the Confederates regrouped and stopped the Federal advance. To their rear, Sigel's initial success turned to failure as Confederate Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch rallied his forces and attacked Sigel's position. Sigel was overrun and his brigade was totally routed with individual units making their way back to Springfield.

After initially withdrawing in front of the Federal attack, the Confederates regrouped and stopped the Federal advance. To their rear, Sigel's initial success turned to failure as Confederate Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch rallied his forces and attacked Sigel's position. Sigel was overrun and his brigade was totally routed with individual units making their way back to Springfield.

To the north on "Bloody Hill" the fighting was intense. As Lyon was leading some of his men into battle, his horse was killed and he was wounded in the head and leg. Later in the fighting, Lyon again was leading his men forward when he was killed by enemy fire.

To the north on "Bloody Hill" the fighting was intense. As Lyon was leading some of his men into battle, his horse was killed and he was wounded in the head and leg. Later in the fighting, Lyon again was leading his men forward when he was killed by enemy fire.  After Lyon's death, command of the Federals went to Major Samuel Sturgis. After consulting with the other Union commanders, Sturgis decided to withdraw north to Springfield. A few days late the Federals would retire northeast to Rolla, Missouri.

After Lyon's death, command of the Federals went to Major Samuel Sturgis. After consulting with the other Union commanders, Sturgis decided to withdraw north to Springfield. A few days late the Federals would retire northeast to Rolla, Missouri.

The Battle of Wilson's Creek did not settle anything. Strategically, Springfield and southwestern Missouri had little value for the Union. After securing the Missouri river, Lyon did not really need to proceed south. He did not need to fight the Battle of Wilson's Creek. Control of the Missouri River was what was of strategic value to the Union. But it was not in Lyon's character to shy away from a fight, even being outnumbered two to one.

- The Federals suffered 1,317 casualties (258 killed, 873 wounded, and 186 missing).

- The Confederates suffered 1,230 casualties (279 killed and 951 wounded).

Ironically, Lyon's body was left behind when the Federals retreated. It was discovered by the Confederates and returned to the Federals in Springfield. Initially, Lyon was buried in Springfield before being disinterred and moved to Connecticut for final burial. An estimated 15,000 people attended his funeral.

Being the first Union general killed in action, Lyon's death made headlines across the nation. On December 24, 1861, a resolution of thanks was passed by the United States Congress for the

"...eminent and patriotic services of the late Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon. The country to whose service he devoted his life will guard and preserve his fame as a part of its own glory. That the Thanks of Congress are hereby given to the brave officers who, under the command of the late general Lyon sustained the honor of the flag and achieved victory against overwhelming numbers at the battle of Springfield, Missouri."

Sites of Interest

- Death of Lyon Marker

Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, 6424 West Farm Road 182 in Republic, Missouri 65738

| Waypoint = |

- Nathaniel Lyon Grave

Phoenixville Cemetery, 35 General Lyon Road, Eastford, Connecticut

| Waypoint = |

- Nathaniel Lyon Monument

Springfield National Cemetery, 1702 East Seminole Street, Springfield, MO 65804

| Waypoint = |

- Bloody Island Historical Marker, Upper Lake, California, 95485

Marker is on Reclamation Road near Redbud Lane, on the right when traveling west.

| Waypoint = 39° 8.938′ N, 122° 53.621′ W |

- Bloody Island (Bo-no-po-ti) Historical Marker, Upper Lake, California, 95485

Marker is at the intersection of Highway 20 and Reclamation Road, on the right when traveling south on Highway 20.

| Waypoint = 39° 8.974′ N, 122° 53.288′ W |

References

- The American Battlefield Protection Program. CWSAC Battle Summaries: Boonville. http://www.nps.gov/abpp/battles/mo001.htm

- The American Battlefield Protection Program. CWSAC Battle Summaries: Wilson's Creek. http://www.nps.gov/hps/abpp/battles/mo004.htm

- Adamson, Hans Christian. Rebellion in Missouri: 1861

" target="_blank">Rebellion in Missouri, 1861 : Nathaniel Lyon and his Army of the West : the rise of Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon, USA, who saved Missouri from secession in the Civil War. Philadelphia : Chilton Co., Book Division, 1961.

- Brooksher, William R. Bloody Hill : The Civil War Battle of Wilson's Creek

" target="_blank">Bloody Hill: The Civil War Battle of Wilson's Creek. Washington: Brassey's, 1995.

- Ethier, Eric. "Firebrand in a Powder Keg: Nathaniel Lyon in St. Louis," Civil War Times, June 2005.

- Gilmore, Donald L. Civil War on the Missouri-Kansas Border

" target="_blank">Civil War on the Missouri-Kansas Border. Gretna: Pelican, 2006.

- Kemp, Hardy A. About Nathaniel Lyon, brigadier general, United States Army Volunteers and Wilson's Creek

" target="_blank">About Nathaniel Lyon, Brigadier General, United States Army Volunteers, and Wilson's Creek. 1978.

- Monachello, Anthony. "Struggle for St. Louis," America's Civil War, March 1998.

- Phillips, Chris. Damned Yankee: The Life of General Nathaniel Lyon

" target="_blank">Damned Yankee : the life of General Nathaniel Lyon. Columbia : University of Missouri Press, 1990.

Back: James G. Blunt

Next: Claiborne Fox Jackson