The Dred Scott Trials

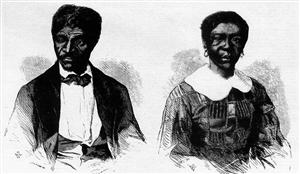

Dred Scott was born a slave at the end of the 18th Century in Virginia. His owner, Peter Blow, moved to Missouri in 1827, taking Dred Scott with him. Some time in 1834 or 1835, Scott was purchased from Blow by Dr. John Emerson, who was an assistant surgeon in the United States Army. In 1834, Emerson was transferred to Rock Island, Illinois and later to Fort Snelling in the Wisconsin Territory. Emerson took Dred Scott with him. While at Fort Snelling, Dred Scott married Harriet Robinson, who was then purchased by Emerson. When Emerson died , his estate including his slaves went to his wife, Irene. [58]

In 1847, Dred Scott sued for his freedom from Emerson's widow, Irene. The defense argued that Dred Scott and his wife should be freed because they had been transported to areas in the United States where slavery was illegal. The jury found in favor of the defendant and against Dred Scott. But his lawyers filed a petition with the court and were granted a second trial because of hearsay testimony given in the 1847 trial. [59]

The second trial happened in January of 1850, and the jury found for the plaintiff, making Scott a freeman. But the defendant appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court, whose decision overturned the jury verdict in March of 1852. Chief Justice Hamilton R. Gamble issued a dissenting opinion. The majority opinion, issued by Justice William Scott, included the following statements: [60]

The courts of one State do not take judicial notice of the laws of other States . . . No State is bound to carry into effect enactments conceived in a spirit hostile to that which pervades her own laws . . . It is a humiliating spectacle, to see the courts of a State confiscating the property of her own citizens by the command of foreign law.

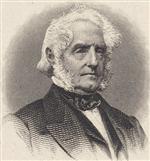

Roswell M. Field, a prominent St. Louis attorney, took up Dred Scott's case in 1853. By this time, ownership of Dred Scott and his family has passed to John F. A. Sanford. Field filed the suit in United States Federal Court in St. Louis, Missouri in November 1853. Before handing the case over to the jury for deliberation, Federal Judge, Robert W. Wells, instructed the jury that the only possible verdict would be for them to rule in favor of the defendant, Sanford. And that's what the jury did, issuing the following verdict: [61]

As to the first issue, not guilty. As to the second issue, that the plaintiff was a negro slave and the property of the defendant. As to the third issue, that Harriet, his wife, and Eliza and Lizzie, his daughters, were negro slaves and the property of the defendant.

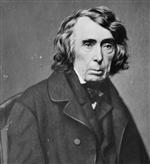

Next stop would be an appeal to the United States Supreme Court, who took up the case of Dred Scott V. John F. A. Sandford in 1856. Roswell M. Field worked on this case but it was argued in Washington by Montgomery Blair. On March 6, 1857, the United States Supreme Court found, 7 to 2, in favor of the defendant. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney wrote the majority opinion, which included the following statements: [62]

The question is simply this: Can a negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such become entitled to all the rights, and privileges, and immunities, guarantied by that instrument to the citizen? One of which rights is the privilege of suing in a court of the United States in the cases specified in the Constitution.

We think they are not, and that they are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word 'citizens' in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States. On the contrary, they were at that time considered as a subordinate and inferior class of beings, who had been subjugated by the dominant race, and, whether emancipated or not, yet remained subject to their authority, and had no rights or privileges but such as those who held the power and the Government might choose to grant them.

The plaintiff in error could not be a citizen of the State of Missouri, within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States, and, consequently, was not entitled to sue in its courts.

In the opinion of the court, the legislation and histories of the times, and the language used in the Declaration of Independence, show, that neither the class of persons who had been imported as slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as a part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument.

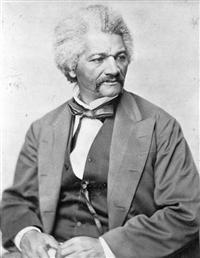

In a speech delivered in New York City on May 14, 1857, Frederick Douglass made the following statements: [63]

This infamous decision of the Slaveholding wing of the Supreme Court maintains that slaves arc within the contemplation of the Constitution of tho United States, property; that slaves are property in the same sense that horses, sheep, and swine are property; that the old doctrine that slavery is a creature of local law is false; that the right of the slaveholder to his slave does not depend upon the local law, but is secured wherever the Constitution of tho United States extends; that Congress has no right to prohibit slavery anywhere; that slavery may go in safety and where under the star-spangled banner; that colored persons of African descent have no rights that white men are bound to respect; that colored men of African descent are not and cannot be citizens of the United States.

The Supreme Court of tho United States is not the only power in this world. It is very great, but the Supreme Court of the Almighty is greater. Judge Taney can do many things, but he cannot perform impossibilities. Ho cannot bale out tho ocean, annihilate this firm old earth, or pluck tho silvery star of liberty from our Northern sky. He may decide, and decide again; but he cannot reverse the decision of the Most High, he cannot change the essential nature of things—making evil good, and good, evil.

The argument here is, that the Constitution comes down to us from a slaveholding period and a slaveholding people; and that, therefore we are bound to suppose that the Constitution recognizes colored persons of African descent, the victims of slavery at that time, as debarred forever from all participation in the benefit of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, although the plain reading of both includes them in their benificent range.

As a man, an American, a citizen, a colored man of both Anglo-Saxon and African descent, I denounce this representation as a most scandalous and devilish perversion of the Constitution, and a brazen mistatement of the facts of history.