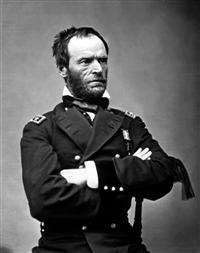

The William T. Sherman Historical Marker

Tour Stop

Directions: The William T. Sherman Historical Marker [ Waypoint = N38 37.716 W90 11.330 ] is a brass plaque located on the brick pillar in the northwest corner of the intersection of Locust Street and Broadway in St. Louis, Missouri 63102.

- It's a short walk of two blocks from the Berthold Mansion tour stop to this tour stop.

- Walk north on Broadway.

- Stay on Broadway as you cross over Olive Street.

- Stay on Broadway as you cross over Locust Street.

- Stop at the corner of Locust and Broadway. The plaque should be on the building just to your left.

Description: The William T. Sherman Historical Marker has the following text:

In March 1861, William Tecumseh Sherman became president of a local railroad based here at Locust and Broadway.

However, upon the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, Sherman quit the railroad to become a leading general in the Union army.

Parts of the novel and movie Gone With The Wind take place during General Sherman's famous march to the Georgia seacoast. He is remembered for burning Atlanta and saying, “War is hell.”

Sherman returned to St Louis in 1883 only to leave seven years later after an angry dispute with city officials over the payment of his water taxes.

Sherman and his wife Ellen are buried in St. Louis Calvary Cemetery.

William T. Sherman has a number of ties to St. Louis. He was the Superintendent at a military academy in Louisiana in 1860 when South Carolina voted to secede from the United States. It was after this event that Sherman made the following remarks to his close friend, David F. Boyd: [68]

You, you the people of the South, believe there can be such a thing as peaceable secession. You don't know what you are doing. I know there can be no such thing . . . If you will have it, the North must fight you for its own preservation. Yes, South Carolina has by this act precipitated war . . . This country will be drenched in blood. God only knows how it will end. Perhaps the liberties of the whole country, of every section and every man will be destroyed, and yet you know that within the Union no man's liberty or property in all the South is endangered . . . Oh, it is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization.

You people speak so lightly of war. You don't know what you are talking about. War is a terrible thing. I know you are a brave, fighting people, but for every day of actual fighting, there are months of marching, exposure and suffering. More men die in war from sickness than are killed in battle. At best war is a frightful loss of life and property, and worse still is the demoralization of the people . . .

You mistake, too, the people of the North. They are a peaceable people, but an earnest people and will fight too, and they are not going to let this country be destroyed without a mighty effort to save it.

After the Louisiana State Militia seized the Federal Arsenal at Baton Rouge on January 9, 1861, Sherman was going to be required to accept a portion of the arms taken from the arsenal. Sherman resigned instead of accepting what he considered to be goods stolen from the United States government. Sherman wrote the Governor about his decision: [69]

Recent events foreshadow a great change, and it becomes all men to choose. If Louisiana withdraw from the Federal Union, I prefer to maintain my allegiance to the Constitution as long as a fragment of it survives; and my longer stay here would be wrong in every sense of the word.

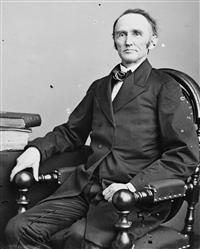

Upon leaving Louisiana, Sherman returned home to Lancaster, Ohio where he found a letter waiting for him from his brother John, who was a US Senator from Ohio, that requested Sherman come to Washington. There was also a letter from his old friend, Major H.S. Turner, offering him a position as president of the Fifth Street Railroad in St. Louis, Missouri. Sherman wrote back to accept the position in St. Louis before heading to Washington to see his brother. Sherman reached Washington less than a week after Abraham Lincoln had been inaugurated as the 16th President of the United States. His brother took Sherman to see President Lincoln. Hearing that Sherman had just come from Louisiana, Lincoln asked Sherman, “How are they getting along down there?” Sherman replied, “They think they are getting along swimmingly—they are preparing for war.” Sherman was very disappointed when Lincoln replied, “Oh, well! I guess we'll manage to keep house.” Sherman returned to Lancaster, Ohio and then went to his new job in St. Louis, Missouri. [70]

On April 1, 1861, Sherman moved his family into a rented house located on Locust Street between Tenth and Eleventh Streets. Thus, William T. Sherman was present in St. Louis when many of the key events of 1861 in Missouri took place. Sherman remembered the situation in his memoirs: [71]

The whole air was full of wars and rumors of wars. The struggle was going on politically for the border States. Even in Missouri, which was a slave State, it was manifest that the Governor of the State, Claiborne Jackson, and all the leading politicians, were for the South in case of a war. The house on the northwest corner of Fifth and Pine was the rebel headquarters, where the rebel flag was hung publicly, and the crowds about the Planters' House were all more or less rebel. There was also a camp in Lindell's Grove, at the end of Olive Street, under command of General D. M. Frost, a Northern man, a graduate of "West Point, in open sympathy with the Southern leaders. This camp was nominally a State camp of instruction, but, beyond doubt, was in the interest of the Southern cause, designed to be used against the national authority in the event of the General Government's attempting to coerce the Southern Confederacy.

On April 6th, Sherman received the following telegram from United States Postmaster General Montgomery Blair: [72]

Will you accept the chief clerkship of the War Department? We will make you assistant Secretary of War when Congress meets.

Sherman immediately replied by telegram, “I cannot accept” followed by a letter stating his reasons: [73]

I have quite a largo family, and when I resigned my place in Louisiana, on account of secession, I had no time to lose; and, therefore, after my hasty visit to Washington, where I saw no chance of employment, I came to St. Louis, have accepted a place in this company, have rented a house, and incurred other obligations, so that I am not at liberty to change.

I thank you for the compliment contained in your offer, and assure you that I wish the Administration all success in its almost impossible task of governing this distracted and anarchical people.

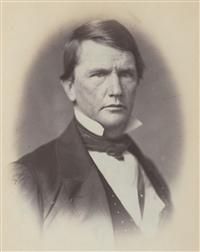

After Fort Sumter, Frank Blair asked Sherman to accept an appointment of Brigadier-General for the purpose of replacing Brigadier-General William S. Harney in command of Federal forces in Missouri. Once again, Sherman declined. But on May 8th, Sherman sent the following letter to US Secretary of War Simon Cameron: [74]

Dear Sir : I hold myself now, as always, prepared to serve my country in the capacity for which I was trained. I did not and will not volunteer for three months, because I cannot throw my family on the cold charity of the world. But for the three-years call, made by the President, an officer can prepare his command and do good service.

I will not volunteer as a soldier, because rightfully or wrongfully I feel unwilling to take a mere private's place, and, having for many years lived in California and Louisiana, the men are not well enough acquainted with me to elect me to my appropriate place.

Should my services be needed, the records of the War Department will enable you to designate the station in which I can render most service.

On May 9th, Sherman would take his children with him to visit the St. Louis Arsenal and described the scene that day: [75]

Within the arsenal wall were drawn up in parallel lines four regiments of the “Home Guards,” and I saw men distributing cartridges to the boxes. I also saw General Lyon running about with his hair in the wind, his pockets full of papers, wild and irregular, but I knew him to be a man of vehement purpose and of determined action. I saw of course that it meant business, but whether for defense or offense I did not know.

The next day, Sherman, along with his son Willie, followed the crowds up to Lindell Grove and was a witness to the Camp Jackson Affair: [76]

[That] morning I . . . heard at every corner of the streets that the "Dutch" were moving on Camp Jackson. People were barricading their houses, and men were running in that direction . . . I felt as much interest as anybody else, but staid at home, took my little son Willie, who was about seven years old, and walked up and down the pavement in front of our house, listening for the sound of musketry or cannon in the direction of Camp Jackson . . . Edging gradually up the street, I was in Olive Street just about Twelfth, when I saw a man running from the direction of Camp Jackson at full speed, calling, as he went, “They've surrendered, they've surrendered!”

A crowd of people was gathered around, calling to the prisoners by name, some hurrahing for Jeff Davis, and others encouraging the troops . . . The man had in his hand a small pistol, which he fired off, and I heard that the ball had struck the leg of one of Osterhaus's staff; the regiment stopped; there was a moment of confusion, when the soldiers of that regiment began to fire over our heads in the grove. I heard the balls cutting the leaves above our heads, and saw several men and women running in all directions, some of whom were wounded. Of course there was a general stampede. Charles Ewing threw Willie on the ground and covered him with his body. Hunter ran behind the hill, and I also threw myself on the ground. The fire ran back from the head of the regiment toward its rear, and as I saw the men reloading their pieces, I jerked Willie up, ran back with him into a gulley which covered us, lay there until I saw that the fire had ceased, and that the column was again moving on, when I took up Willie and started back for home round by way of Market Street.

On May 14, 1861, William T. Sherman received word that he had been appointed Colonel, Thirteenth Regular Infantry and was needed in Washington immediately. After the war's end, Major-General William T. Sherman returned to St. Louis as the commander of the Military Division of the Missouri, returning to St. Louis in July of 1865. Sherman did not remain in St. Louis for long. [77]

In 1869, after Grant was inaugurated as the 18th President of the United States, Sherman was appointed as the General of the Army. In 1874, Sherman received permission from President Grant to move his headquarters from Washington to St. Louis, which he did in October. Sherman would retire from the army to St. Louis on November 1, 1883. William T. Sherman is buried next to his wife, Eleanor “Ellen” Boyle Ewing Sherman, in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri. [78]

Back: The Berthold Mansion

Next: The St. Louis Mercantile Library