The Camp Jackson Interpretive Sign

Tour Stop

Directions: The former site of Camp Jackson is located on the campus of St. Louis University in St. Louis,Missouri. The Camp Jackson Interpretive Sign [ Waypoint = N38 38.139 W90 13.957 ] is located on the campus of St. Louis University just east of Grand Blvd between Olive Street and Laclede Avenue.

- Return to your car and drive out to Lindell Boulevard and turn right (east).

- After about 2.1 miles, there is a parking garage on the right. You will have crossed Grand Blvd and the street's name will have changed to Olive Street.

- Park in visitor parking in the Olive Garage. Link to St. Louis University's parking regulations.

- Walk to the Camp Jackson Interpretive Sign near the corner of Grand Blvd and Laclede Avenue.

Follow this link to see an image of Camp Jackson in 1861 at the Missouri Civil War Museum's website.

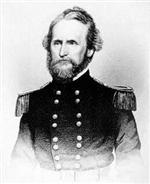

Description: It was this location, on My 10, 1861, that Brigadier-General Nathaniel Lyon led about 6,500 newly mustered in Federal Volunteers to surround an encampment of about 900 Missouri State Militia under the command of Brigadier-General Daniel M. Frost. Although events leading up to the Camp Jackson Affair had begun following the 1860 elections, things really started moving after the surrender of Fort Sumter.

The Camp Jackson Interpretive Sign [Waypoint = N38 38.139 W90 13.957 ] has the following text:

At this location there occurred on May 10, 1861 an incident that has become known as the Camp Jackson Affair. On that day an encampment of the First Brigade of the Missouri state militia was surrounded and captured by volunteers in the service of the federal government. As the captured militia members were being marched away a clash took place between the federal volunteers and an angry mob that left a number of spectators either dead or wounded. This incident greatly inflamed feelings in St. Louis and throughout the state and galvanized many previously wavering Missourians to choose one side or the other in the impending civil war.

The extraordinary set of circumstances that led troops in service of the federal government to take the extreme measure of capturing a seemingly legal encampment of the state militia can only be understood within the larger context of Missouri's relation to the Union during the tension-filled early months of 1861. Most Missourians in 1861 adopted a stance of "conditional unionism." Such men dominated the state convention that met in February and March and decided against secession and in favor of a stance of neutrality.

The powerful secessionist minority was led by the newly elected governor, Claiborne Jackson. Leading the opposition was the unconditional unionist, Frank Blair, a Republican member of Congress from St. Louis.

During the early months of 1861, paramilitary organizations were created in St. Louis by both sides; unionists were formed as Wide Awakes, while the secessionists styled themselves Minute Men. Both groups kept their eyes on the St. Louis Arsenal. This federal armory contained a store of 38,000 muskets, 45 tons of powder, and 11 cannon. In the arsenal were weapons aplenty to equip a large army and seize control of the state.

In February, the Union cause was boosted by the arrival of Capt. Nathaniel Lyon, a Connecticut-born West Pointer who vehemently hated secessionists. During the next two months, Lyon energetically set about to strengthen the defenses of the arsenal and organize and train the Wide Awakes, who were being transformed into home guard companies. The Minute Men were not idle either; Lyon and Blair constantly heard rumors of plots by the secessionists to seize the arsenal.

In the tense weeks following the firing on Fort Sumter on April 12, after Governor Jackson defiantly refused Lincoln's call for troops, Lyon and Blair stepped forward to fill this void. Soon some 10,000 men, mostly German Americans, were mustered into federal service. As a further precaution, Lyons arranged in late April to transfer most of the arms in the arsenal to Illinois.

In the face of the aggressive actions by the St. Louis unionists, the secessionists also stepped up their efforts. On April 20, they seized the small arsenal at Liberty, Missouri. At the same time, Jackson secretly wrote to Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, requesting siege guns with which to reduce the stout walls that ringed the St. Louis arsenal. He also issued orders for the pro-southern militia organizations in the state to muster for their six-day annual encampments. The main objective of the muster was to counter the buildup of union troops in St. Louis. It was with this in mind that Camp Jackson came into being.

Camp Jackson was located in a large parklike area known as Lindell's Grove, situated on what was then the western edge of the city. On May 6, 898 men of the first brigade, including 300 Minute Men, assembled for the encampment. Two days later, the siege guns, which had been seized from the federal arsenal at Baton Rouge, La., arrived in St. Louis aboard a steamboat and were immediately hauled to Camp Jackson. Lyon's spies quickly informed him of this clandestine delivery.

The following day, May 9, Lyon decided to scout the camp. Disguised as Frank Blair's mother-in-law, he was driven around the camp where he observed the crated guns and noted streets named in honor of the prominent Confederates Davis and Beauregard. Armed with this evidence, Lyon was able to convince the unionist Committee of Safety that it was essential to capture the camp and eliminate the threat that an organized body of secessionist troops could pose to St. Louis.

On May 10, Lyon's force of 6,000 volunteers was assembled at the arsenal. He divided this force into three detachments and ordered them to proceed by different routes to Camp Jackson. By 3:30 p.m. the camp was completely surrounded. Lyon immediately sent a note to the commanding officer of the camp. Gen. Daniel M. Frost, demanding the surrender of his forces. As General Frost was outnumbered eight to one, he had little choice but to accede to Lyon's demand.

Some time was consumed organizing the captured militia for the march back to the arsenal. During this delay, word of the capture of Camp Jackson spread rapidly through the city and a large crowd began to gather at Lindell's Grove. In the crowd were numerous southern sympathizers. As the crowd magnified in size it became increasingly belligerent. They first hurled epithets at the "damned dutch," then clods of dirt, stones, and brickbats. Soon after the column of troops and their prisoners began to march down Olive Street, shots rang out and Capt. Constantin Blandovski fell mortally wounded. In response, the volunteers began to fire volleys into the crowd, which stampeded in panic, leaving 28 mostly innocent spectators dead and numerous others wounded.

Finally, at around 6 p.m., it was finally possible to resume marching back to the arsenal; the next day most of them were paroled.

The news of Camp Jackson electrified the entire state. The state legislature, amidst rumors of an imminent attack upon Jefferson City by Lyon and Blair, met in an extraordinary all-night session; they gave Governor Jackson the absolute powers he long sought to create and equip a state guard capable of resisting federal invasion. Many wavering unionists now flocked to the secessionist camp. Foremost among these was Sterling Price, the popular former governor and Mexican War hero who had recently served as president of the convention that voted to keep Missouri in the Union. Jackson immediately placed him in charge of the newly created state guard with the rank of major general.

As for the overall significance of the Camp Jackson Affair, Bruce Catton, the eminent Civil War historian, has offered a good summary:

"Blair and Lyon had won the civil war in St. Louis before it really got started, which was just what they set out to do, but as far as the rest of the state was concerned, they had won nothing; they had simply made more civil war inevitable. The fighting in St. Louis was clear warning that the middle of the road was no path for Missourians. No longer would carefree militiamen lounge picturesquely in a picnic-ground camp... Now they would fight, and other men would fight against them, and no part of the United States would know greater bitterness or misery."