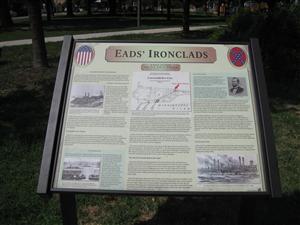

Eads' Ironclads Interpretive Sign

Tour Stop

Directions: The Eads' Ironclads Interpretive Sign [ Waypoint = N38 32.774 W90 15.565 ] is located in South St. Louis Square Park.

- You will need to get headed south on Broadway, but will have to go around the block after exiting Bellerive Park.

- Head west on Bellerive Boulevard (you will take a bridge that crosses over Broadway).

- Take the first left (south) onto Pennsylvania Avenue.

- Take the first left (east) onto Dover Street.

- After about 1.3 miles, South St. Louis Square Park will be on the right.

- The interpretive sign is along the sidewalk in the southern end of the park.

Description: James B. Eads would build many gun boats for the Union. One of his ironclads, the USS Cairo, was salvaged and is currently on display at the Vicksburg National Military Park in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

The Eads' Ironclads Interpretive Sign has the following text:

Carondelet and the Eads Ironclads

On Oct. 12, 1861, the ironclad gunboat USS Carondelet slid down the ways at James Eads' Union Iron Works in the village of Carondelet, south of St Louis. It was the first ironclad warship built by the United States, launched more than three months before the famed USS Monitor. During the course of the Civil War, Eads' Union Iron Works would furnish the Union with more ironclad warships than any other boatyard in the West.

"The Key to The Whole Situation"

When war broke out in April 1861, the Union found its vital trade route down the Mississippi River blocked by Confederate forts and batteries. President Abraham Lincoln was aware of the river's importance. Reopening it would split the South and provide a highway of invasion into the Confederate heartland. "The Mississippi River," he declared, "is the backbone of the Rebellion; it is the key to the whole situation." To deal with the formidable Confederate forts, Lincoln sought advice from one of the most knowledgeable rivermen on the Mississippi - James Buchanan Eads of St. Louis.

Eads, a 41-year-old, self-taught engineer, knew European navies were experimenting with ironclad warships. He advised building a fleet of armored gunboats to attack enemy forts at close range and overwhelm them with point-blank fire. Lincoln was enthusiastic, and soon government engineer Samuel Pook was developing a design for a river ironclad. In August 1861 Eads won a construction contract for seven gunboats with the low bid of $89,600 per boat. He agreed to complete all seven in a little over two months, and to forfeit $250 per boat for each day late.

Eads Builds Pook's Turtles

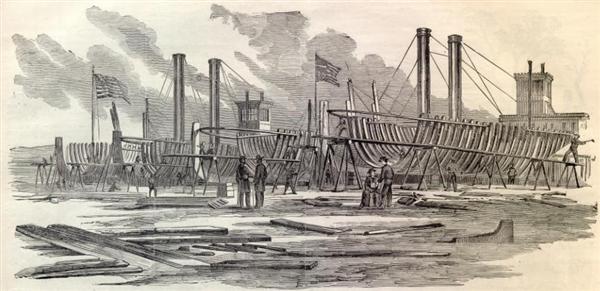

Eads heed a daunting task. The blockade of the Mississippi had forced Northern mills, machine shops and foundries to close, and their workers to disperse. Eads began telegraphing contracts for iron, lumber, boat stores and machinery to suppliers throughout the region. Businesses soon reopened and new ones were established; 13 sawmills in seven states began preparing timber for the gunboats, three of which were to be built at Mound City, Ill., and four at Carondelet.

In Carondelet, Eads leased the construction yards of the Carondelet Marine Railway, a facility that featured a rail system for moving boats in and out of the water. He renamed it the Union Iron Works, and within two weeks employed 500 men. Work went on around the clock, but problems slowed construction; suitable iron was difficult to find; threats of sabotage caused security to be increased; workmen threatened to strike; and weaknesses in Pook's design required last-minute alterations. Eads' main problem, however, was financial. He had exhausted his personal fortune to begin the project and the government failed to pay when stipulated. Eads borrowed from banks and friends to complete the contract, but did not receive full payment until the following year.

In spite of setbacks, the first gunboat, USS Carondelet, was launched at Carondelet on Oct. 12, 1861; only two days past deadline. It was soon followed by the St. Louis, Louisville and Pittsburgh, then by the boats built at Mound City - the Cincinnati, Mound City and Cairo. Additional months were spent assembling crews and arming the odd-looking crafts, which were dubbed "Pook's Turtles" by the newspapers.

The seven ironclads first saw action in the spring of 1862 when the Union captured Forts Henry and Donelson, New Madrid and Island No. 10. Fort Pillow fell on June 4, and two days later the Confederate river fleet was destroyed in a naval battle off Memphis. Vicksburg, the final obstacle, surrendered in July 1863, leaving the Mississippi open to its mouth. The Eads ironclads contributed a great deal to the success of those campaigns.

“Give Me the Ironclads Built by Mr. Eads”

Despite his difficulty receiving payment for the Pook gunboats, Eads continued to win contracts and build ironclads. His Carondelet boatyard became the most complete facility of its land in the country. Its 20 acres boasted a gas plant, engine shops, sawmills and machinery for shaping armor plate. Seventy forges were at work; blacksmiths flung still-glowing rivets to boys who caught them in cans and rushed them to be hammered home. Shelters protected the workmen from sun and rain and torches lighted their work at night.

Eads paid well, giving cash bonuses for overtime, but by 1864 war-weariness and inflation led to labor unrest throughout the North. In St. Louis, machinists, blacksmiths, tailors and shoemakers struck for higher wages and to end the hiring of less-experienced workers for lower pay. The government intervened, and in April placed the workers of St. Louis under martial law. Picketing was banned and unions were outlawed; infantry stood ready to enforce the order. The strikers had no choice but to return to their jobs.

Work continued at the Carondelet yards, which produced to ironclads during the course of the war - the four Pook gunboats; the Essex (converted from a ferry boat); the Neosho and Osage (shallow-draft, single-turret river monitors); and the Winnebago, Kickapoo and Milwaukee (large, propeller-driven monitors with twin turrets). In addition, the yards built 38 mortar boats (armored rafts mounting a 13-inch mortar) and converted numerous steamboats into “tin clads” (lightly armored patrol vessels). Other boatyards in St. Louis also produced ironclads and tin clads. In all, the Union deployed 23 ironclad warships on Western waters - more than half built at Carondelet or St. Louis.

Eads worked constantly to improve his vessels: For his monitors he designed a steam-powered turret, superior to the manually powered turret of the original Monitor. It allowed a faster rate of fire and required fewer crew. The Navy, however, insisted on the manual turret, but allowed Eads to equip two of his twin-turret monitors with one of his own turrets. He was to replace them at his own expense if they proved unacceptable. On Aug. 5, 1864, two of Eads' twin-turret monitors fought their way into Mobile Bay with the fleet of Adm. David Farragut and proved the superiority of the Eads turret. “Only give me the ironclads built by Mr. Eads,” Farragut proclaimed, “and I will find out how far Providence is with us.”

Eads fell ill early in 1864. His doctors believed he was beyond recovery, but he improved and took his family overseas for a rest. Not one to be idle, Eads, on behalf of the government, visited the navies of Europe, where he was hailed for his innovative work in naval engineering.

Eads Boatyard Today

James Eads' Carondelet boatyard furnished the Union Navy with the heart of its river fleet. The original ways were removed in 1933 and nothing now remains of the facility. The site, however, is still used for marine transportation, as it currently functions as a loading and off loading site for barge traffic

The Pook Ironclads

The first seven ironclads were designed by engineer Samuel Pook. They looked like nothing else in the Navy; each was flat-bottomed, 175 feet long by 51 feet wide and drew no more than 6 feet of water. Atop the deck stood a low deck house, or casemate, with sloping sides. To protect the engines, the casemate was armored in front and amidships with 2 1/2 inches of iron over 26 inches of oak. Thirteen heavy guns were mounted in the casemate - three firing forward, four to each side and two aft. Each boat was operated by a crew of about 160 officers and men. One gunboat sailor described the vessels as "of the mud-turtle school of architecture, with just a dash of pollywog treatment" But, he added grimly, "they struck terror into every guilty soul"

James Buchanan Eads

James Eads was among the most important engineers and inventors of the 19th century. Born May 23, 1820, in Lawrenceburg, Ind., he came to St. Louis with his family in 1833. Although impoverished, he taught himself mathematics and engineering. He learned about the Mississippi River while clerking on a steamboat. At age 12, he invented a diving bell and entered the marine salvage business.

By 1857, he had earned a fortune, but too-rapid decompression while diving crippled his health, forcing him into early retirement. He recovered, and helped the Union win the Civil War by designing and building innovative ironclad warships. His greatest triumphs were the completion in 1874 of the Eads Bridge in St. Louis - the first bridge to span the Mississippi - and a jetty system to protect the Mississippi's mouth from silting over. He died on March 8, 1887 after a life of brilliant accomplishment.