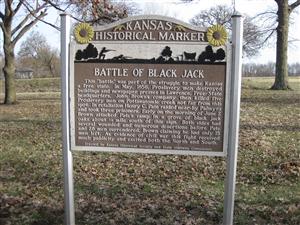

The Battle of Black Jack Historical Marker

Tour Stop

- From Interstate 35 take exit 202 and head north towards Edgerton, Kansas 66021.

- Travel north on Sunflower Road for about 1.4 miles.

- After crossing the railroad tracks, the name changes to E Nelson Street.

- After about 0.8 miles, turn right (north) onto W 8th Street.

- After 0.2 miles, turn left (west) onto 199th Street / US Highway 56.

- After about 6 miles, the marker is located just east of E 2000th Road in a roadside turnout on the south side of US Highway 56.

Description: The marker was erected by Kansas State Historical Society and State Highway Commission and has the following text:

“The 'battle' was part of the struggle to make Kansas a free state. In May, 1856, Proslavery men destroyed buildings and newspaper presses in Lawrence, Free-State headquarters. John Brown's company then killed five Proslavery men on Pottawatomie creek not far from this spot. In retaliation Henry C. Pate raided nearby Palmyra and took three prisoners. Early on the morning of June 2 Brown attacked Pate's camp in a grove of black jack oaks about 1/4 mile south of this sign. Both sides had several wounded and numerous desertions before Pate and 28 men surrendered, Brown claiming he had only 15 men left. As evidence of civil war this fight received much publicity and excited both the North and South.”

Missourians were incensed when they heard what had happened during the Pottawatomie Massacre. Seeking revenge, Henry Clay Pate took a group of about 75 Shannon's Sharpshooters and entered Kansas to find and punish the free state perpetrators. Pate was certain that old John Brown was responsible for the killings along Pottawatomie Creek. He planned find Brown and either capture him or kill him. Arriving in the vicinity of Osawatomie, Kansas, Pate was able to make prisoners of John Brown, Jr. and Jason Brown, both sons of old John Brown. Ironically, neither of them had been involved in the Pottawatomie Massacre. A few days later, Pate turned his prisoners over to a company of US Cavalry under the command of Captain Wood.

Missourians were incensed when they heard what had happened during the Pottawatomie Massacre. Seeking revenge, Henry Clay Pate took a group of about 75 Shannon's Sharpshooters and entered Kansas to find and punish the free state perpetrators. Pate was certain that old John Brown was responsible for the killings along Pottawatomie Creek. He planned find Brown and either capture him or kill him. Arriving in the vicinity of Osawatomie, Kansas, Pate was able to make prisoners of John Brown, Jr. and Jason Brown, both sons of old John Brown. Ironically, neither of them had been involved in the Pottawatomie Massacre. A few days later, Pate turned his prisoners over to a company of US Cavalry under the command of Captain Wood.

While searching for old John Brown, Pate went on a rampage against the free state settlers, plundering and burning their cabins. During this time, Pate and his men were camped along Captain's Creek near the the settlement of Black Jack (near present day Baldwin City, Kansas 66006). Old John Brown decided he needed to go after the Missourians and put a stop to their raiding. He was able to pull together a small group of about 12 free state men, including his sons, Frederick, Owen and Watson. On June 1, 1856, Brown and his men had reached Prairie City, Kansas. Here, Brown met up with Captain Samuel T. Shore and his company of about 20 free state militia. They both agreed to begin searching for Pate's camp, which was supposed to be somewhere near Black Jack.

On June 1, 1856, Henry C. Pate and his men had raided the free-state settlement of Palmyra, Kansas and took two men prisoner. When finished in Palmyra, Pate and his men withdrew to their camp along Captain's Creek. Here they settled in for the night. Brown and Shore would discover Pate's camp early on the morning of June 2nd. Brown's son, Owen, later wrote an article for the Springfield Republican in which he described their first seeing the Missourians' camp:

“On reaching the high ground where their guard had stood we could plainly see the Missourians’ camp, a half-mile distant, with their tents and covered wagons drawn up in front, and a number of horses and mules picketed on the higher ground beyond. This camp (under command of Capt. H. C. Pate, as we found later) was on a point of land lying between two ravines, at this time dry; but at other times they had an outlet into a larger ravine, the latter lying between us and Pate’s camp (the ground descending toward us).”

The two sides began firing at one another, both sides using the ravines for cover. Owen Brown described the initial engagement:

“Father ordered us to form a skirmish line, and Pate’s men commenced firing at us. When within rifle range Capt Shore ordered his men to halt, and, though in a very exposed position, they bravely began in earnest to return the fire. Father directed us to reserve our fire, and to follow him in a diagonal direction into the larger ravine. Pate’s men gave us the full benefit of their shooting, their bullets cutting the grass around us in a lively way. Though I do not think I was much scared, I noticed I felt very light on my feet, as if marching fast would be no effort.

“We crossed the ravine and Father placed us at short range, behind a natural bank in the bend of the ravine, so that their wagons afforded them no protection from our fire. During the time we were taking this position Capt Shore kept up a constant firing, and by the time our men were located, he ordered his men to lie down and shoot from that position. At much shorter range we shot at any of Pate’s men we could see, and into their tents. Within 10 or 15 minutes the Missourians began to run from their wagons and tents over into the opposite ravine for greater securing, and Capt Shore’s men came running, a few at a time, to where we were.”

After two or three hours of fighting, Shore's men were running out of ammunition. After consulting with old John Brown, Shore and his men withdrew. During the fighting, some of Pate's men had withdrawn from the fighting and headed back to Missouri. Now John Brown was down to having only about 12 men. He was up against maybe 30 still fighting along side Pate. About this time, in the words of Owen Brown:

“[My] brother Frederick, hearing the firing, could not longer content himself to stay back with the horses, but mounting one of them and brandishing a sword, rode round Pate’s camp on a full run, and called aloud, saying, 'Father, we have got them surrounded, and have cut off their communications.' A number of shots were fired at Fred without hitting him or his horse. A few moments after this a ramrod with a white handkerchief fastened to it was raised by the Missourians as a flag of truce, and the firing ceased.”

Henry C. Pate's force was also running low on ammunition and decided to try and talk his way out the predicament. At first, Pate had sent a subordinate out to meet with the free state men. But John Brown refused to talk with anyone by Pate. So Pate went out under the flag of truce with one of the free state settlers he had taken prisoner on the previous day. Pate said that he was a duly appointed representative of the United States government and was searching for individuals for which he had warrants of arrest. Brown dismissed all of this and told Pate he would accept nothing but Pate's unconditional surrender. Owen Brown described the encounter:

“Capt Pate took the flag, and, bringing with him a free-state prisoner whom he had captured at another time, came to where he stood and said, 'I come out to tell you that we are government officers sent out in pursuit of criminals, and to let you know that you are fighting against the United States.' ... Father replied: 'If this is all you have to say, I have something to say to you. I demand of you an unconditional surrender.' Then Father ordered us to go with him and Pate to where the latter had left his men, and we came up nearly together. Father repeated to Lieut Brockett, of the Missouri men, what he had just said to Pate. Brockett replied, “We don’t surrender unless our captain gives the order.” His men then cocked and leveled their guns on us. ... Father raised his large army-sized Colt’s revolver and, pointing it within two feet of Pate’s heart, said to him, “Give the order!” and he did. ... The rest of their arms, ammunition, wagons, horses, etc., were at once given up to us, and the prisoners put under guard.”

Henry Clay Pate later wrote an article in the St. Louis Republican about his encounter with John Brown:

“...A flag of truce was sent out, and an interview with the captain requested. Captain Brown advanced and sent for me. I approached him and made known the fact that I was acting under the orders of the U. S. Marshal, and was only in search of persons for whom writs of arrest had been issued, and that I wished to make a proposition. He replied that he would hear no proposals, and that he wanted an unconditional surrender. I asked for fifteen minutes to answer. He refused, and I was taken prisoner under the flag of truce.

“Brown and his confederates were the men engaged in the Pottawattomie massacre, and whom I was authorized to arrest. In fact, as I say to my friends, I went to take Old Brown, and Old Brown took me.”

John Brown and his small force ended up with 23 prisoners. On their way back to Prairie City, they met Captain Shore who was returning with reinforcements. John Brown would end up negotiating an exchange of prisoners. He exchanged Henry C. Pate and Brockett to get his sons, John, Jr. and Jason, released from Federal custody. However, a few days later, Pate and the other prisoners were freed by US forces under the command of Colonel Edwin Sumner. Jason Brown was released from custody later in June but John Brown, Jr. was taken to Camp Sackett where the other Free State Prisoners were being held. He not released from custody until September in 1856.

John Brown and his small force ended up with 23 prisoners. On their way back to Prairie City, they met Captain Shore who was returning with reinforcements. John Brown would end up negotiating an exchange of prisoners. He exchanged Henry C. Pate and Brockett to get his sons, John, Jr. and Jason, released from Federal custody. However, a few days later, Pate and the other prisoners were freed by US forces under the command of Colonel Edwin Sumner. Jason Brown was released from custody later in June but John Brown, Jr. was taken to Camp Sackett where the other Free State Prisoners were being held. He not released from custody until September in 1856.