Directions: The entrance to Calvary Cemetery [ Waypoint = N38 41.681 W90 14.311 ] is located at 5239 West Florissant Avenue in St. Louis, Missouri 63115.

Description: This tour will focus on four grave sites of interest concerning St. Louis and the Civil War. Be sure to stop in at the visitor center near the entrance to pick up a map of the cemetery. Here is a link to a PDF of the map on the cemetery's website. For additional Civil War graves of interest in Calvary Cemetery, consult William C. Winter's Civil War in St. Louis listed in the Tour's References.

The roads in the cemetery are not always well marked. Try to pay attention to the Section numbers as you try to locate the grave markers.

The Daniel M. Frost Grave at Calvary Cemetery [ Waypoint = N38 41.797 W90 14.170 ] is located in Section 18, Lot 48.

A New York native, Daniel M. Frost was a West Point graduate who had served with distinction in the Mexican–American War. He left the army and moved to St. Louis in 1851 to get married and get started in business. In 1858 he was appointed as the Brigadier-General of the First Brigade of Missouri Volunteer Militia. The First Brigade would see action in western Missouri against incursions from Kansas Territory led by James Montgomery. [164]

According to Thomas L. Snead, who at the time was the aide-de-camp to Missouri Governor Claiborne Jackson, had this to say about Frost: [165]

Neither he nor his men had any very precise idea of the part which they would be called upon to take in the event of war between the North and the South. Like himself, they were, for the most part, Union men, but opposed to the subjugation of the South. Few of them expected to use their arms against the United States; fewer still to use them against the South. They were citizens and soldiers of Missouri and were ready to fight for her. Further than that they did not then look, or care to look.

Daniel Frost played a key role in the first half of 1861. Frost understood that the arms and munitions stored at the Federal Arsenal in St. Louis were very important to the fate of Missouri in 1861. Again, according to Thomas L. Snead: [166]

No one comprehended more clearly than General Frost the necessity which compelled Missouri to keep the arsenal and its stores within her grasp, if she would arm and equip her people; as arm them she must, sooner or later, whether to fight for the Union, or against it, or to maintain her own neutrality. This necessity he made manifest to the Governor, and was by him authorized to seize the arsenal, whenever the occasion might require such decisive action.

Daniel Frost, Brigadier-General, Missouri State Militia visited the St. Louis Arsenal on January 24, 1861 to speak with its commander, US Army Major William H. Bell. Bell was a North Carolina native who was sympathetic to the Southern cause. Frost described the results of the meeting to Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson in a note: [167]

I have just returned from the arsenal . . . I found the Major everything that you or I could desire. He assured me that he considered that Missouri had, whenever the time came, a right to claim it as being on her soil . He asserted his determination to defend it against any and all irresponsible mobs, come from whence they might, but at the same time gave me to understand that he would not attempt any defense against the proper State authorities . . . In a word, the Major is with us, where he ought to be.

This arsenal, if properly looked after, will be everything to our State, and I intend to look after it; very quietly, however.

However, Frost's plans for the arsenal were thwarted by US Army Captain Nathaniel Lyon, who arrived in St. Louis at the beginning of February in 1861. On May 10th, Brigadier-General Daniel Frost would surrender his force of 800 Missouri State Militia encamped at Camp Jackson to a greatly superior force of newly mustered Federal Volunteers under the command of Brigadier-General Nathaniel Lyon. Frost made the followoing reply to Lyon's demand of surrender: [168]

SIR: I never for a moment having conceived the idea that so illegal and unconstitutional a demand as I have just received from you would be made by an officer of the U.S. Army I am wholly unprepared to defend my command from this unwarranted attack, and shall therefore be forced to comply with your demand.

Receiving a parole after his capture at Camp Jackson, Frost was not exchanged until September 1861 following the Battle of Lexington. Frost was exchanged for Colonel James A. Mulligan, who had been in command of the Federal forces captured at Lexington. Daniel Frost accepted an appointment as a Brigadier-General in the Confederate Army in March 1862. Frost was in command of Frost's Division in the Trans-Mississippi Army of Major-General Thomas Hindman at the Battle of Prairie Grove in 1863. Later that year, Frost would take an unauthorized leave of absence to assist his wife, who had been banished from their home in St. Louis by Federal authorities. Frost would remain in Canada with his family for the remainder of the war, returning to Missouri in 1865. [169]

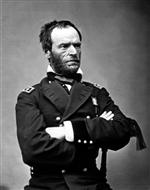

William T. Sherman's Grave [ Waypoint = N38 41.909 W90 14.217 ] is located in Section 17, Lot 8.

William T. Sherman has a number of ties to St. Louis. He was the Superintendent at a military academy in Louisiana in 1860 when South Carolina voted to secede from the United States. After the Louisiana State Militia seized the Federal Arsenal at Baton Rouge on January 9, 1861, Sherman was going to be required to accept a portion of the arms taken from the arsenal. Sherman resigned instead of accepting what he considered to be goods stolen from the United States government. Upon leaving Louisiana, Sherman returned home to Lancaster, Ohio where he found a letter waiting for him from his brother John, who was a US Senator from Ohio, that requested Sherman come to Washington. There was also a letter from his old friend, Major H.S. Turner, offering him a position as president of the Fifth Street Railroad in St. Louis, Missouri. Sherman wrote back to accept the position in St. Louis before heading to Washington to see his brother. Sherman reached Washington less than a week after Abraham Lincoln had been inaugurated as the 16th President of the United States. His brother took Sherman to see President Lincoln. Hearing that Sherman had just come from Louisiana, Lincoln asked Sherman, “How are they getting along down there?” Sherman replied, “They think they are getting along swimmingly—they are preparing for war.” Sherman was very disappointed when Lincoln replied, “Oh, well! I guess we'll manage to keep house.” Sherman returned to Lancaster, Ohio and then went to his new job in St. Louis, Missouri. [170]

On April 1, 1861, Sherman moved his family into a rented house located on Locust Street between Tenth and Eleventh Streets. Thus, William T. Sherman was present in St. Louis when many of the key events of 1861 in Missouri took place. Sherman remembered the situation in his memoirs: [171]

The whole air was full of wars and rumors of wars. The struggle was going on politically for the border States. Even in Missouri, which was a slave State, it was manifest that the Governor of the State, Claiborne Jackson, and all the leading politicians, were for the South in case of a war. The house on the northwest corner of Fifth and Pine was the rebel headquarters, where the rebel flag was hung publicly, and the crowds about the Planters' House were all more or less rebel. There was also a camp in Lindell's Grove, at the end of Olive Street, under command of General D. M. Frost, a Northern man, a graduate of "West Point, in open sympathy with the Southern leaders. This camp was nominally a State camp of instruction, but, beyond doubt, was in the interest of the Southern cause, designed to be used against the national authority in the event of the General Government's attempting to coerce the Southern Confederacy.

On April 6th, Sherman received the following telegram from United States Postmaster General Montgomery Blair: [172]

Will you accept the chief clerkship of the War Department? We will make you assistant Secretary of War when Congress meets.

Sherman immediately replied by telegram, “I cannot accept” followed by a letter stating his reasons: [173]

I have quite a large family, and when I resigned my place in Louisiana, on account of secession, I had no time to lose; and, therefore, after my hasty visit to Washington, where I saw no chance of employment, I came to St. Louis, have accepted a place in this company, have rented a house, and incurred other obligations, so that I am not at liberty to change.

I thank you for the compliment contained in your offer, and assure you that I wish the Administration all success in its almost impossible task of governing this distracted and anarchical people.

After Fort Sumter, Frank Blair asked Sherman to accept an appointment of Brigadier-General for the purpose of replacing Brigadier-General William S. Harney in command of Federal forces in Missouri. Once again, Sherman declined. But on May 8th, Sherman sent the following letter to US Secretary of War Simon Cameron: [174]

Dear Sir : I hold myself now, as always, prepared to serve my country in the capacity for which I was trained. I did not and will not volunteer for three months, because I cannot throw my family on the cold charity of the world. But for the three-years call, made by the President, an officer can prepare his command and do good service.

I will not volunteer as a soldier, because rightfully or wrongfully I feel unwilling to take a mere private's place, and, having for many years lived in California and Louisiana, the men are not well enough acquainted with me to elect me to my appropriate place.

Should my services be needed, the records of the War Department will enable you to designate the station in which I can render most service.

On May 9th, Sherman would take his children with him to visit the St. Louis Arsenal and described the scene that day: [175]

Within the arsenal wall were drawn up in parallel lines four regiments of the “Home Guards,” and I saw men distributing cartridges to the boxes. I also saw General Lyon running about with his hair in the wind, his pockets full of papers, wild and irregular, but I knew him to be a man of vehement purpose and of determined action. I saw of course that it meant business, but whether for defense or offense I did not know

The next day, Sherman, along with his son Willie, followed the crowds up to Lindell Grove and was a witness to the Camp Jackson Affair: [176]

[That] morning I . . . heard at every corner of the streets that the "Dutch" were moving on Camp Jackson. People were barricading their houses, and men were running in that direction . . . I felt as much interest as anybody else, but staid at home, took my little son Willie, who was about seven years old, and walked up and down the pavement in front of our house, listening for the sound of musketry or cannon in the direction of Camp Jackson . . . Edging gradually up the street, I was in Olive Street just about Twelfth, when I saw a man running from the direction of Camp Jackson at full speed, calling, as he went, “They've surrendered, they've surrendered!”

A crowd of people was gathered around, calling to the prisoners by name, some hurrahing for Jeff Davis, and others encouraging the troops . . . The man had in his hand a small pistol, which he fired off, and I heard that the ball had struck the leg of one of Osterhaus's staff; the regiment stopped; there was a moment of confusion, when the soldiers of that regiment began to fire over our heads in the grove. I heard the balls cutting the leaves above our heads, and saw several men and women running in all directions, some of whom were wounded. Of course there was a general stampede. Charles Ewing threw Willie on the ground and covered him with his body. Hunter ran behind the hill, and I also threw myself on the ground. The fire ran back from the head of the regiment toward its rear, and as I saw the men reloading their pieces, I jerked Willie up, ran back with him into a gulley which covered us, lay there until I saw that the fire had ceased, and that the column was again moving on, when I took up Willie and started back for home round by way of Market Street.

On May 14, 1861, William T. Sherman received word that he had been appointed Colonel, Thirteenth Regular Infantry and was needed in Washington immediately. After the war's end, Major-General William T. Sherman returned to St. Louis as the commander of the Military Division of the Missouri, returning to St. Louis in July of 1865. Sherman did not remain in St. Louis for long. [177]

In 1869, after Grant was inaugurated as the 18th President of the United States, Sherman was appointed as the General of the Army. In 1874, Sherman received permission from President Grant to move his headquarters from Washington to St. Louis, which he did in October. Sherman would retire from the army to St. Louis on November 1, 1883. William T. Sherman is buried next to his wife, Eleanor “Ellen” Boyle Ewing Sherman, in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri. [178]

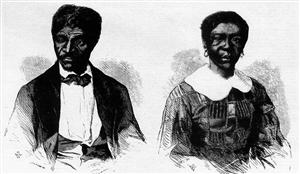

The Dred Scott Grave at Calvary Cemetery [ Waypoint = N38 42.003 W90 13.917 ] is located in Section 1, Lot 77.

Dred Scott was born a slave at the end of the 18th Century in Virginia. His owner, Peter Blow, moved to Missouri in 1827, taking Dred Scott with him. Some time in 1834 or 1835, Scott was purchased from Blow by Dr. John Emerson, who was an assistant surgeon in the United States Army. In 1834, Emerson was transferred to Rock Island, Illinois and later to Fort Snelling in the Wisconsin Territory. Emerson took Dred Scott with him. While at Fort Snelling, Dred Scott married Harriet Robinson, who was then purchased by Emerson. When Emerson died , his estate including his slaves went to his wife, Irene. [179]

In 1847, Dred Scott sued for his freedom from Emerson's widow, Irene. Over the next ten years, there was a series of trials before the case landed before the United States Supreme Court. On March 6, 1857, the United States Supreme Court found, 7 to 2, in favor of the defendant. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney wrote the majority opinion in which he stated that Dred Scott was not a citizen of the United States and was ordered back into slavery: [180]

We think they are not, and that they are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word 'citizens' in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States.

The Thomas C. Reynolds Grave [ Waypoint = N38 41.987 W90 13.790 ] is located in Section 1, Lot 231.

Born in South Carolina, Thomas Caute Reynolds moved to St. Louis, Missouri in 1850. Reynolds ran as a Democrat and was elected Lieutenant Governor of Missouri in November 1860. Along with newly elected Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson, Reynolds was a secessionist who believed the State of Missouri would vote to secede and join her fellow slave-holding states. In January 1861 Reynolds published a letter calling for the General Assembly to authorize a State convention and a State Militia. In addition, he wrote the following: [181]

In our system a State is its people, citizens compose that people, and to use force against citizens acting by State authority is to coerce the State and to wage war against it. To levy tribute, molest commerce, or hold fortresses, are as much acts of war as to bombard a city.

In June 1861, following the Battle of Boonville, Reynolds was forced into exile along with most of the rest of the State Government. In July 1861, the Missouri State Convention reconvened in Jefferson City, Missouri and voted to vacate the offices of Governor and Lieutenant Governor. The convention delegates then voted Hamilton Rowan Gamble to be Provisional Governor and Willard Preble Hall to Provisional Lieutenant Governor. After Claiborne Fox Jackson died in December 1862, Thomas C. Reynolds returned from a self-imposed exile in south Carolina to assume the position of Governor of Missouri in the Confederate States of America. Reynolds would be on the move constantly as the war in the West continued to go against the Confederates. He eventually ended up establishing his headquarters in Marshall, Texas, where he remained until the end of the war. [182]

In December 1864, following the disaster of Price's Missouri Raid, Governor Reynolds published a letter in defense of Major-General John S. Marmaduke and Brigadier-General William L. Cabell, who had both been captured at the Battle of Mine Creek. Instead, Governor Reynolds placed the blame on the Confederate defeats squarely on the shoulders of Major-General Sterling Price. In this December 17, 1864 letter to the public, Reynolds made the following statements: [183]

The responsibility for disgraces and disasters . . . of the army at the time [are] justly attributed to the glaring mismanagement and distressing mental and physical military incapacity of Major General Sterling Price.

After the war, Reynolds went into exile in Mexico with a number of other Confederates. Reynolds returned to St. Louis in 1869 and was elected to the Missouri Legislature in 1874. Reynolds killed himself in 1887 by jumping down an elevator shaft at the Customs House in St. Louis.