Major General Sterling Price reported that his casualties in the fighting in and around Lexington were 25 killed and 72 wounded. He also reported that the Missouri State Guard took about 3,500 prisoners following the surrender of Union forces by Colonel Mulligan. The Federals reported 39 killed and 120 wounded. Most believe the relatively low Missouri State Guard casualties from this battle were the result of Price's patience and the clever use of the hemp bales for cover. The low casualty rate on the Union side resulted from the sturdy entrenchments built by the Federals.

Major General Sterling Price reported that his casualties in the fighting in and around Lexington were 25 killed and 72 wounded. He also reported that the Missouri State Guard took about 3,500 prisoners following the surrender of Union forces by Colonel Mulligan. The Federals reported 39 killed and 120 wounded. Most believe the relatively low Missouri State Guard casualties from this battle were the result of Price's patience and the clever use of the hemp bales for cover. The low casualty rate on the Union side resulted from the sturdy entrenchments built by the Federals.

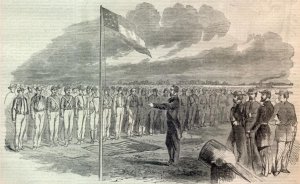

After the surrender, Missouri Governor Claiborne Jackson spoke to the Federal troops, as reported in Harper's Weekly:

After the surrender, Missouri Governor Claiborne Jackson spoke to the Federal troops, as reported in Harper's Weekly:

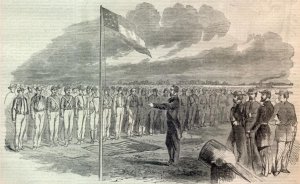

"The rebel Governor Jackson ordered Mulligan's Brigade to be drawn up in solid column to hear a speech from him. He then addressed them in harsh language, demanding what business they had to make war in the State of Missouri, adding that when Missouri needed troops from Illinois, she would ask for them. After upbraiding them for some length of time, this wretched traitor at last told them they might go home, when they dispersed with feelings which can be more easily imagined than described. If Governor Jackson falls into the hands of any Illinois Volunteers he will have a hard time."

"The rebel Governor Jackson ordered Mulligan's Brigade to be drawn up in solid column to hear a speech from him. He then addressed them in harsh language, demanding what business they had to make war in the State of Missouri, adding that when Missouri needed troops from Illinois, she would ask for them. After upbraiding them for some length of time, this wretched traitor at last told them they might go home, when they dispersed with feelings which can be more easily imagined than described. If Governor Jackson falls into the hands of any Illinois Volunteers he will have a hard time."

Price's official report provides additional insight into what his victory had accomplished:

"The visible fruits of this almost bloodless victory are very great about 3,500 prisoners, among whom are Colonels Mulligan, Marshall, Peabody, White, and Grover, Major Van Horn, and 118 other commissioned officers, 5 pieces of artillery and 2 mortars, over 3,000 stands of infantry arms, a large number of sabers, about 750 horses, many sets of cavalry equipments, wagons, teams, and ammunition, more than $100,000 worth of commissary stores, and a large amount of other property. In addition to all this, I obtained the restoration of the great seal of the State and the public records, which had been stolen from their proper custodian, and about $900,000 in money, of which the bank at this place had been robbed, and which I have caused to be returned to it."

However, Price would not be able to remain in Lexington. He position there was very precarious and he had to withdraw south. Even with the victory, Price had been unable to achieve one of his main objectives, recruiting Missourians over to the Southern cause. Serving as Price's Chief Ordnance Officer, Colonel J. F. Snyder later wrote that

"...the substantial Missourians were more interested in the conservation of their property and scalps, than in sacrificing anything for the defense of any mere abstract principle. Yet, when it became known that the Union garrison of 2640 men had surrendered, large contingents of Missouri chivalry did rush into Lexington, frantic with enthusiasm, and loud in their vapory declarations of loyalty to our cause. ... Then came word that the Federals were on their way to dislodge us, and our new recruits began to scatter. Some of them remained with us - for awhile. General Price left Lexington with an army of 22,000 men, two thirds of whom were unarmed and unorganized. He crossed the Osage, going south, with barely 12,000; and less than 8,000 of us went into winter quarters at Springfield."

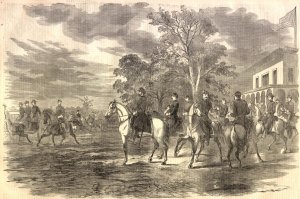

Union Major General John Charles Fremont had been faced with inadequate resources since being named to the command of the Federal Western Department in July 1861. Even as late as September 22, 1861, two days after Mulligan had surrendered, Fremont continued to send out orders to try and get reinforcements to besieged garrison at Lexington. On September 23rd, it became clear to Fremont that Mulligan had surrendered on September 20th, Fremont realized that the disaster Lexington placed his job in jeopardy. He decided to act. On September 23rd, Fremont sent the following order to Brigadier General Samuel Sturgis:

Union Major General John Charles Fremont had been faced with inadequate resources since being named to the command of the Federal Western Department in July 1861. Even as late as September 22, 1861, two days after Mulligan had surrendered, Fremont continued to send out orders to try and get reinforcements to besieged garrison at Lexington. On September 23rd, it became clear to Fremont that Mulligan had surrendered on September 20th, Fremont realized that the disaster Lexington placed his job in jeopardy. He decided to act. On September 23rd, Fremont sent the following order to Brigadier General Samuel Sturgis:

"Lexington having surrendered, a combined attack upon the rebels infesting the country between Springfield and Lexington will be made by the troops under my command without delay. You are directed to watch the enemy as narrowly as possible, to hold Kansas City at all hazards, and to keep me constantly informed of his and your movements."

Fremont also notified Washington on the same day:

Fremont also notified Washington on the same day:

"I have telegram from Brookfield that Lexington has fallen into Price's hands, he having cut off Mulligans supply of water. Re-enforcements 4,000 strong, under Sturgis, by capture of ferry-boats, had no means of crossing the river in time. Lanes force from the southwest and Davis from the southeast, upwards of 11,000, could not get there in time. I am taking the field myself, and hope to destroy the enemy either before or after the junction of forces under McCulloch. Please notify the President immediately."

Fremont received the following reply from General-in-Chief Winfield Scott.

"Your dispatch of this day is received. The President is glad you are hastening to the scene of action. His words are, He expects you to repair the disaster at Lexington without loss of time."

Unfortunately for Fremont, it was too little, too late. While "in the field," Fremont was relieved of command on November 2, 1861 by order of President Lincoln.

Major General Sterling Price reported that his casualties in the fighting in and around Lexington were 25 killed and 72 wounded. He also reported that the Missouri State Guard took about 3,500 prisoners following the surrender of Union forces by Colonel Mulligan. The Federals reported 39 killed and 120 wounded. Most believe the relatively low Missouri State Guard casualties from this battle were the result of Price's patience and the clever use of the hemp bales for cover. The low casualty rate on the Union side resulted from the sturdy entrenchments built by the Federals.

Major General Sterling Price reported that his casualties in the fighting in and around Lexington were 25 killed and 72 wounded. He also reported that the Missouri State Guard took about 3,500 prisoners following the surrender of Union forces by Colonel Mulligan. The Federals reported 39 killed and 120 wounded. Most believe the relatively low Missouri State Guard casualties from this battle were the result of Price's patience and the clever use of the hemp bales for cover. The low casualty rate on the Union side resulted from the sturdy entrenchments built by the Federals. After the surrender, Missouri Governor

After the surrender, Missouri Governor  "The rebel Governor Jackson ordered Mulligan's Brigade to be drawn up in solid column to hear a speech from him. He then addressed them in harsh language, demanding what business they had to make war in the State of Missouri, adding that when Missouri needed troops from Illinois, she would ask for them. After upbraiding them for some length of time, this wretched traitor at last told them they might go home, when they dispersed with feelings which can be more easily imagined than described. If Governor Jackson falls into the hands of any Illinois Volunteers he will have a hard time."

"The rebel Governor Jackson ordered Mulligan's Brigade to be drawn up in solid column to hear a speech from him. He then addressed them in harsh language, demanding what business they had to make war in the State of Missouri, adding that when Missouri needed troops from Illinois, she would ask for them. After upbraiding them for some length of time, this wretched traitor at last told them they might go home, when they dispersed with feelings which can be more easily imagined than described. If Governor Jackson falls into the hands of any Illinois Volunteers he will have a hard time." Union Major General

Union Major General  Fremont also notified Washington on the same day:

Fremont also notified Washington on the same day: