Directions: The Battle of Boonville Historical Marker and Interpretive Sign [ Waypoint = N38 58.655 W92 44.027 ] are a good place to start this tour. The interpretive sign provides an overview of the battle and a map of the events of June 17, 1861. They are located along East Morgan Street about 0.1 miles east of 10th Street in Boonville, Missouri 65233. The marker and sign are located next to one another near the northwest corner of the Boonville Correctional Center at 1216 East Morgan Street.

If coming from the west...

If coming from the east...

Description: You are standing just south of where the Boonville Fair Grounds were located in 1861. It was at this location that the final few minutes of fighting took place. Because the people of Jefferson City were primarily Unionist, Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson had ordered the State armory relocated to Boonville. They had chosen the fair grounds as the location for the State's powder and military stores. [30]

The following is excerpted from an eyewitness account reported in the Missouri Democrat newspaper: [31]

“The McDowell now came along up in the rear and off to the right from our troops, and having a more distant view of the enemy, from the river, and observing their intention of making another stand at the Fair grounds, one mile east of here, where the State has an armory extemporized, Captain Voester again sent them his compliments from the old howitzer's mouth, which, with a couple of shots from Captain Totten and a volley from Lothrop's detachment of rifles, scattered the now thoroughly alarmed enemy in all directions. Their flight through the village commenced soon after eight o'clock and continued until after eleven. Some three hundred crossed the river, many went south, but the bulk kept on westwardly. A good many persons were taken at the different points of battle, but it is believed the enemy secured none of ours.

Captain Richardson had landed below, and, with the support of the howitzer from the steamer McDowell, captured their battery, consisting of two six-pounders (with which they intended to sink our fleet), twenty prisoners, one caisson, and eight horses with military saddles. The enemy did not fire a shot from their cannon.

After passing the Fair grounds, our troops came slowly toward town. They were met on the east side of the creek by Judge Miller, of the District Court, and other prominent citizens, bearing a flag of truce, in order to assure our troops of friendly feelings sustained by three-fourths of the inhabitants, and, if possible, prevent the shedding of innocent blood. They were met cordially by General Lyon and Colonel Blair, who promised, if no resistance was made to their entrance, that no harm need be feared. Major O'Brien soon joined the party from the city, and formally surrendered it to the Federal forces. The troops then advanced, headed by the Major and General Lyon, and were met at the principal street by a party bearing and waving that beautiful emblem under which our armies gather and march forth, conquering and to conquer. The flag party cheered the troops, who lustily returned the compliment. American flags are now quite thick on the street, and secessionists are nowhere.”

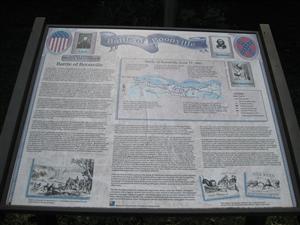

The text of The Battle of Boonville Interpretive Sign reads as follows:

The text of The Battle of Boonville Historical Interpretive Sign reads as follows:

A State Divided: The Civil War in Missouri

On June 17, 1861, the Battle of Boonville at this and other locations along this road. By most standards of warfare, the Battle of Boonville was more truly a skirmish or demonstration than a full blown battle. But small conflicts can sometimes have large consequences, and such was the case for the outcome of the Battle of Boonville. The battle was not only one of the first flash points of conflict in the rapidly escalating Civil War, but it also helped decide in favor of the Union the then uncertain question of Missouri's status. Ex-Confederate, Thomas L. Snead, summarized the consequences of the Battle of Boonville in 1888: "Insignificant as was this engagement in a military aspect, it was in fact a stunning blow to the Southern Rights' people of the State, and one which did incalculable and unending injury to the Confederates."

Months of mounting tension between Unionist and Secessionist factions preceded the outbreak of hostilities at Boonville. A pr-Southern faction, led by Gov. Claiborne Fox Jackson, was at work organizing a military force, the State Guard, to be placed under the command of Maj. Gen. Sterling Price. Backed by a powerful state military force, Gov. Jackson intended to lead Missouri into the Confederacy. Determined to thwart Jackson's designs was a strong Unionist faction based in St. Louis and led by Congressman Frank Blair, Jr. and Gen. Nathaniel Lyon. The final break between these struggling factions came at a meeting, held June 11, 1861, between Jackson, Price, Blair and Lyon, at the Planter's House in St. Louis. Lyon concluded this stormy meeting by declaring that a state of war now existed between Jackson's treasonous government and the United States.

Jackson and Price, fearing that Lyon's army would soon be on their heels, quickly left this meeting and returned to Jefferson City to organize a hasty evacuation of the Capitol. Reasoning that Jefferson City was too pro-Union to defend, Gov. Jackson and Gen. Price ordered their volunteers to muster at either Boonville or Lexington, both strongholds of Southern sentiment. If Boonville could be held for a couple of weeks while Southern volunteers massed at Lexington, the State Guard might be transformed into an army capable of holding Missouri for the Confederacy.

On June 13, Jackson evacuated the capital city. Two days later, Lyon, Blair, and 2,000 soldiers arrived in four boats to take control of Jefferson City. Lyon was well aware of the danger that could come allowing Price and Jackson enough breathing space to assemble and train an army. Determined to prevent this by keeping the enemy on the run, Lyon continued steaming on to Boonville with 1,700 men.

Fearing that enemy artillery was emplaced on the bluffs near Boonville, Lyon disembarked his force some eight miles below town. At 7 a.m. Lyon set his army in motion. A march of two miles across the floodplain of the Missouri River led to a point where the road they were on, the Rocheport Road, began a gradual rise into the surrounding river hills. As the force started its ascent, State Guard pickets opened fire, and then fell back.

A mile to the west, an advanced detachment of four or five hundred State Guardsmen awaited Lyon's approach. Earlier that morning the Southern volunteers had moved out of their encampment, called variously Camp Vest or Camp Bacon, to take up their position on Rocheport Road. The commander of the guardsmen, Col. John Sappington Marmaduke, was not optimistic about the outcome of the coming fight. He knew that his total force of 1,500 poorly armed and untrained men was no match for Lyon's disciplined and well-equipped soldiers. Marmaduke urged Gov. Jackson to concentrate his forces further south, at Warsaw, where battle with the Federals could be had with terms more favorable to the Southerners. With a victory in hand, they might be able to launch a campaign to drive the Federals from the state. Jackson, however, was unwilling to depart from Boonville without offering a show of resistance, and insisted they make a stand whatever the odds.

The position chosen for the Southern stand was along a lane that intersected Rocheport Road about a mile west of where the pickets first fired on Lyon's approaching army. On the northeast corner of the intersection stood a brick house behind which was a wheat field. Concealing themselves behind the house, its outbuildings and fences, and a thicket of woods, the state forces had a good position to pour fire into the exposed ranks of the advancing Federals.

The main portion of the battle opened at approximately 8 a.m., with a brisk shelling of the rebel positions by Lyon's artillery,under the command of Captain Totten. The artillery occupied the center of Lyon's column while infantry steadily advanced on either flank. For a while, according to one newspaper account, the air whined with bullets as each side unleashed volleys at one another. Totten soon found his range, and two cannon balls came crashing into the brick house, and others poured into the Southern position. Thus dislodged, the defenders fell back across the fences and through the wheat field. The Southerners were able to stitch together a new line near the brow of a hill, advance some twenty paces and open fire. Lyon's troops, now rapidly advancing, were compelled to cross a stretch of open ground. A body of the enemy concealed in a grove unleashed what was described a a galling fire. This created the few casualties suffered by the Federal side. Again, Totten's artillery was pressed into service while the troops on both flanks pushed the attack. It seemed at this point that the skirmish might assume the magnitude of a full-fledged battle, but the lack of arms and discipline of the Southern force began to take their toll. The superior military preparation and fire power of the Federal side soon overpowered the ill-prepared Southerners and Marmaduke gave the order to retreat. The battle had lasted little more than 20 minutes. The withdrawing Southerners made an attempt to maintain some semblance of order as they pulled back, firing at their pursuers from any available cover. Their retreat, however, progressively degenerated into a disorderly stampeded.

While the Federal infantry pressed the attack, the McDowell steamed upriver to a point opposite Camp Bacon and began to shell the position with an eight-inch howitzer. This discouraged the Southerners from any attempt to linger in the encampment long enough to gather their belongings. The Federals marched into the hastily evacuated camp to find food still on tables and much equipment left behind including 1,200 pairs of shoes, assorted tents, blankets and other items.

The final Southern stand was made at the fairgrounds, about a mile east of town. During the evacuation of the Capitol, Jackson had moved the State armory to this location. The river-based howitzer was once again called into service and lobbed shells onto the Southern position while the Union infantry closed in rapidly. The retreating Southerners were forced to leave behind their only two artillery pieces, a pair of six-pound cannons that were never used against the enemy.

By 11 a.m., Gen. Lyon was riding into Boonville to receive the surrender of the town from a local delegation of citizens. At the same time, Jackson was exiting the other end of town, bound for southwest Missouri to link up with Price and his troops who were at the same time evacuating Lexington. Word of the Boonville rout convinced Price that the rich and friendly Missouri River valley was no longer a safe haven. Lyon's rapid action had denied Price and Jackson the precious time they needed to build up their army in he Missouri heartland.

As battles went, Boonville was clearly a small affair. Three Southerners were killed and five to nine wounded, while the Federal toll came to five killed, seven wounded. Probably few battles of so minor a scale reaped such large results as did the Boonville triumph for Lyon. He had toppled the state government and sent the governor, general assembly and State Guard fleeing southward. Furthermore, the Missouri River was now a Federal highway that barred potential recruits in northern Missouri from joining Price and Jackson in southwest Missouri.

Eminent Civil War historian, Bruce Catton, summarized the significance of what Lyon had accomplished: “This fight at Boonville, the slightest of skirmishes by later standards, was in fact a very consequential victory for the Federal government. Gov. Jackson had been knocked loose from the control of his state, and the chance that Missouri could be carried bodily into the Southern Confederacy had gone glimmering. Jackson's administration was now, in effect, a government-in-exile, fleeing down the roads toward the Arkansas border, a disorganized body that would need a great deal of help from Jefferson Davis's government before it could give any substantial help in return.”

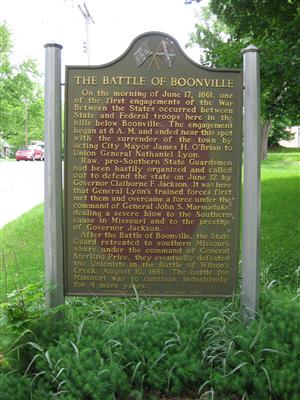

The text of The Battle of Boonville Historical Marker reads as follows:

On the morning of June 17, 1861, one of the first engagements of the War Between The States occurred between State and Federal troops here in the hills below Boonville. The engagement began at 8 A. M. and ended near this spot with the surrender of the town by acting City Mayor James H. O'Brian to Union General Nathaniel Lyon.

Raw, pro-Southern State Guardsmen had been hastily organized and called out to defend the state on June 12 by Governor Claiborne F. Jackson. It was here that General Lyon's trained forces first met them and overcame a force under the command of General John S. Marmaduke, dealing a severe blow to the Southern cause in Missouri and to the prestige of Governor Jackson.

After the Battle of Boonville, the State Guard retreated to southern Missouri, where under the command of General Sterling Price, they eventually defeated the Unionists in the Battle of Wilson's Creek, August 10, 1861. The battle for Missouri was to continue indecisively for 4 more years.

Erected by Adams Dairy, September, 1958.